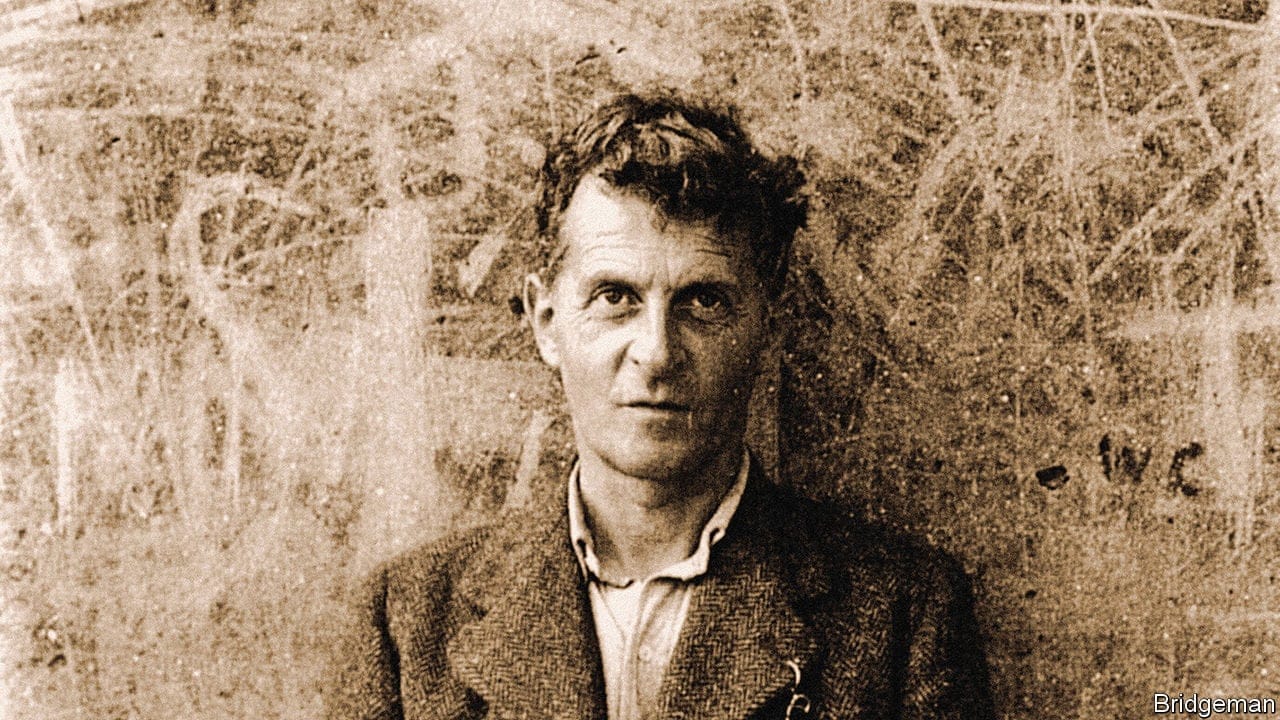

A really-quick intro to Wittgenstein

The only philosopher whose toilet I've personally used

Let’s play a game. You go first.

You don’t know how to make a move? Well, neither do I. Let’s figure it out as we go.

If we don’t agree on the rules ahead of time, are we really playing a game? If we are, what gives meaning to the moves we make?

This scenario might seem wild and weird, but according to philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein it's not too far from how we use language every day. In his groundbreaking work Philosophical Investigations, published posthumously from a sack of notes he carried around with him until he died, Wittgenstein challenges us to reconsider our most basic assumptions about language, meaning, and understanding.

At the heart of Philosophical Investigations is the idea that meaning is not a fixed, inherent property of words but instead arises from their use within specific contexts. This insight is powerful and profound and really hard to hold on to, so I’m going to do my honest best to introduce some of the key implications of this below.

1. Language-Games: Meaning Through Use

One of Wittgenstein’s central ideas is the concept of language-games. He argues that words get their meaning from their use in particular social practices, the ‘language-games’ in question. Just as different games have their own rules and purposes, different contexts of language-use follow their own implicit rules.

For instance, on a construction site, when a builder calls out 'Slab!', it's not merely naming an object - it's a command for the assistant to bring a slab. Similarly, when we write 'apples' on a grocery list, we're not describing fruit - we're creating an instruction to purchase apples. These are distinct language games, each with its own rules and purposes.

In the same way, the word 'game' means something different depending on whether we are discussing chess, soccer, wordplay, or the weird anything-goes thing at the top of this article. Its meaning is determined by the context in which it is used.

In short, there is no single, overarching system of rules that defines the meaning of words—each use of language is a game with its own unique set of rules, rules which nobody agreed upon and which are always in at least a little bit of flux.

2. Private Language and the Nature of Understanding

Wittgenstein famously critiques the idea of a private language—a language that only an individual can understand. He argues that if the meaning of words comes from shared practices, then a private language, understood only by a single person, is impossible. If you invented a new word that only you could understand, how would you ever know if you used it incorrectly? How could it have a useful definition at all if nobody could ever correct you?

Wittgenstein's argument against private language has far-reaching implications. If a truly private language is impossible, it suggests that:

Meaning is inherently social: Our inner experiences, sensations, and thoughts can only have meaning when connected to publicly observable behavior and shared practices. We learn to describe our inner lives in childhood, replacing inarticulate cries with saying “I’m sad”. Language precedes our mental life, not the other way around.

The mind is not a "black box": We can't have purely internal, incommunicable experiences. This challenges the Cartesian view of the mind as separate from the external world.

Skepticism about other minds is misguided: If meaning requires shared practices, we can't coherently doubt whether others have minds like our own.

Language learning is a social process: We don't simply attach words to pre-existing, private mental contents. Instead, we learn the meaning of words by participating in shared forms of life.

This view radically reshapes our understanding of consciousness, subjectivity, and intersubjectivity, suggesting that our inner lives are inextricably linked to our social existence.

3. The Limits of Philosophical Theory: Family Resemblances

Another powerful idea Wittgenstein introduces is the notion of family resemblances. Instead of trying to define concepts with precise boundaries, he suggests that many philosophical concepts are better understood as having overlapping similarities, like family traits.

This picture of family resemblances marks a significant departure from traditional philosophical approaches to definition. Historically, philosophers sought to define concepts by identifying necessary and sufficient conditions - a set of essential features that all instances of a concept must share. A traditional definition of 'game' might attempt to list properties that all games must have, such as 'involving competition' or 'following rules.'

However, Wittgenstein argues that many concepts resist this type of rigid definition. Instead of searching for a common essence, he suggests we look for overlapping similarities, much like traits shared among family members. Just as siblings might share some features but not others, instances of a concept may be related without all sharing a single defining characteristic.

This approach allows for more flexible, context-dependent understandings of concepts. It acknowledges the fuzzy boundaries and varied uses of words in real-life language, rather than trying to force them into artificially precise categories. For instance, while chess and hide-and-seek are both games, they share few features beyond being rule-governed activities pursued for enjoyment. The family resemblance approach captures this diversity while still explaining why we group these activities under the same concept.

By rejecting the search for essential definitions, Wittgenstein challenges centuries of philosophical tradition and offers a new way to understand how language and concepts work in practice.

4. Forms of Life: The Social Basis of Meaning

Wittgenstein argues that language and meaning are rooted in forms of life—the broader cultural and social contexts that shape how we act and communicate. Our shared human practices provide the foundation for how we understand and use language.

This is a radical departure from earlier views of language as something detached from the messy reality of human existence. Instead, meaning is deeply intertwined with our everyday activities and interactions, which shape how language works in practice.

Consider the phrase 'It's raining cats and dogs.' In English-speaking cultures, this idiom is understood as a colorful way of describing heavy rainfall. However, this phrase would be nonsensical if translated literally into many other languages.

The meaning of this idiom is deeply rooted in the English language's form of life - the shared cultural context, history, and practices of English speakers. It reflects a particular way of using metaphorical language to describe weather phenomena, which may not exist in cultures with different linguistic traditions or climatic conditions.

For instance:

In some arid regions, where rain is rare, the language might lack elaborate expressions for different types of rainfall.

In cultures where animals hold different symbolic meanings, the use of cats and dogs in this context might be confusing or even offensive.

Some languages might use entirely different metaphors to express the same idea. For example, in Norwegian, they might say 'It's raining female trolls' ('Det regner trollkjerringer') to describe heavy rain.

This example illustrates how our shared practices and cultural context (our 'form of life') shape not just the words we use, but how we use them and the meanings we derive from them. The phrase 'It's raining cats and dogs' only makes sense within a particular linguistic and cultural framework - it's inseparable from the form of life in which it evolved and is used.

5. Therapeutic Philosophy: Dissolving Confusion

Wittgenstein viewed philosophy as a therapeutic activity rather than a quest for theoretical knowledge. He believed that many philosophical problems arise from misunderstandings of how language works. By paying close attention to the way words are used in real-life contexts, we can dissolve the confusion that gives rise to these problems.

This approach is sometimes described as therapeutic philosophy—a way of clearing up the conceptual confusions that lead to traditional philosophical puzzles. Instead of seeking to construct complex theories, Wittgenstein helps us see that many philosophical issues disappear once we stop misusing language.

A prime example of Wittgenstein's therapeutic approach is his treatment of the philosophical problem of other minds. This problem asks: How can we know that other people have minds and inner experiences like our own?

Traditionally, philosophers have approached this as a serious epistemological issue, proposing various arguments and theories to bridge the apparent gap between our own conscious experience and our knowledge of others' mental states.

Wittgenstein, however, argues that this 'problem' arises from a misuse of language. Here's how he dissolves it:

He points out that in our everyday language games, we don't typically doubt whether others have minds. The very idea of 'other minds' presupposes their existence.

He shows that the concept of 'mind' or 'mental states' gets its meaning from how we use it in our shared forms of life. We learn to attribute mental states to others as part of learning language and participating in social practices.

He argues that the philosophical question 'How do we know others have minds?' doesn't actually arise in any real context of language use. It's a question that only seems meaningful when we abstract language from its practical contexts.

By analyzing how we actually use mental state terms in everyday life, Wittgenstein shows that our certainty about others' minds is not based on evidence or inference, but is part of the framework within which we operate.

Thus, Wittgenstein doesn't solve the problem of other minds; he dissolves it by showing that it's not a genuine problem at all, but a conceptual confusion arising from philosophical misuse of language. This exemplifies his therapeutic approach: clearing away philosophical puzzles by carefully examining how language actually works in practice.

Conclusion: Wittgenstein’s Vision of Philosophy

Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations represents a paradigm shift in how we approach language, meaning, and philosophical inquiry itself. By introducing concepts like language-games, family resemblances, and forms of life, Wittgenstein challenges us to see language not as a fixed system of meanings, but as a diverse set of practices deeply embedded in our social lives and cultural contexts.

His rejection of a private language and emphasis on the social nature of meaning forces us to reconsider fundamental assumptions about mind, knowledge, and understanding. Meanwhile, his notion of family resemblances offers a more flexible way to understand concepts, freeing us from the rigid categorizations that often lead to philosophical dead ends.

Perhaps most radically, Wittgenstein's therapeutic approach to philosophy suggests that many longstanding philosophical problems are not deep mysteries to be solved, but confusions to be clarified through careful attention to how we actually use language. It invites us to look at the world around us with fresh eyes, to pay attention to the rich tapestry of language uses that shape our understanding, to approach philosophical questions not as puzzles to be solved but as knots to be carefully untangled.

It invites us to see how any feelings of isolation are illusory impossibilities. We are always already with other people. That knowledge brings a kind of peace and happiness that philosophers have spent many lifetimes fighting to attain.