The Good Son's Revenge

What Nietzsche and Jesus both get right about ressentiment

It’s party time for everyone, except for you. Your brother is home, safe and sound and accounted for after spitting in your father’s face and running away. He rejected everything your family stands for in the strongest possible terms and for years, ruining his life completely. Once he had nowhere else to go he came crawling back, and what does your father do? He throws him a party.

Where, then, is your party? You, who followed the rules perfectly. You, who honored your father as your brother ran away. You, who alone stand fit to be his heir. Why did you even bother? Why follow the rules at all? Why him, and not you?

In Luke 15:25‑32, Jesus tells the parable of the prodigal son and zooms in after the father welcomes him home. Returning from another dutiful day in the fields, the elder son “heard music and dancing.” A servant explains the celebration. Instantly the elder son’s body language shifts: he refuses to enter the party, turning the public party into a private protest. When the father comes out, the son vents and presents his accounting: “Lo, these many years do I serve thee, neither transgressed I at any time thy commandment: and yet thou never gavest me a kid, that I might make merry with my friends: as soon as this thy son was come, which hath devoured thy living with harlots, thou hast killed for him the fatted calf.”

His complaint isn’t about justice in the abstract, it’s about the wound of comparison. Obedience has instantly transformed into envy, cloaked in the language of moral accounting.

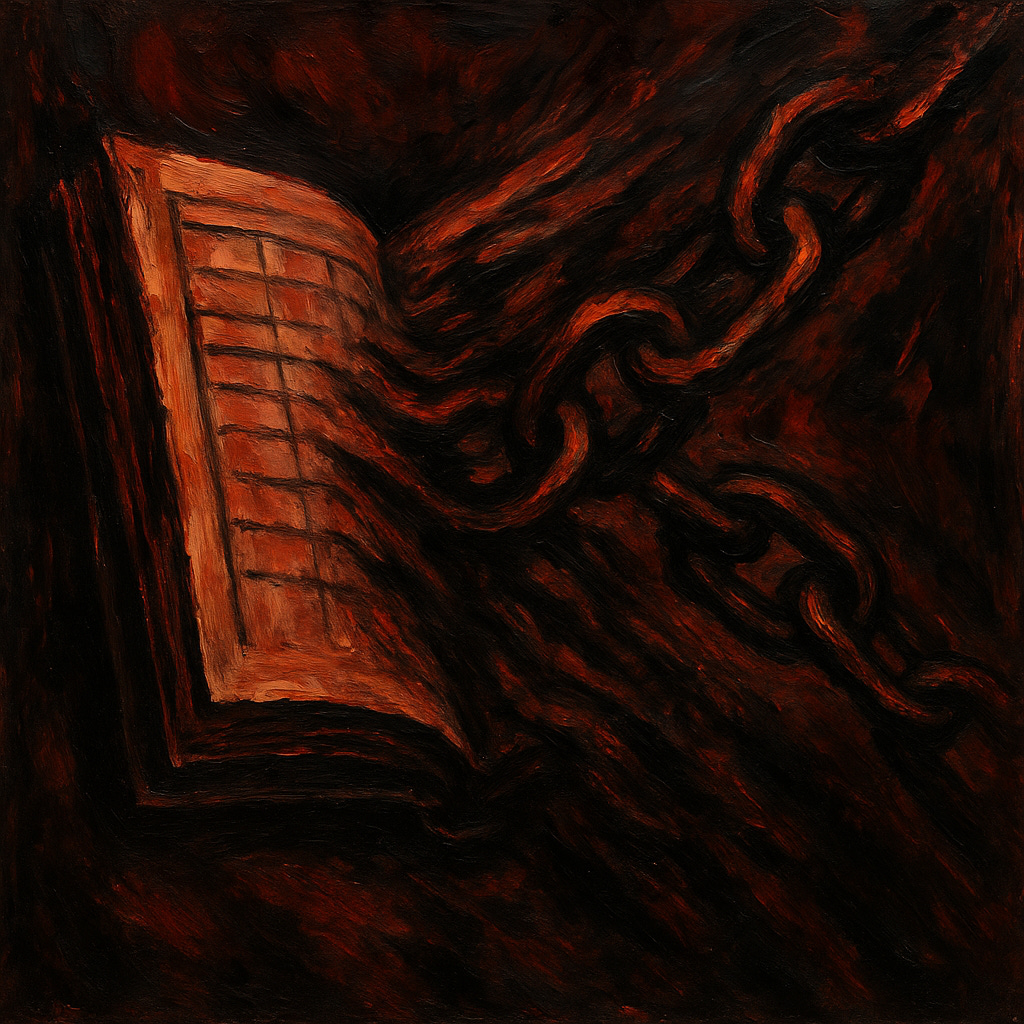

In On the Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche labels this emotion ressentiment: a re‑feeling of injury that cannot discharge itself in action, so it retaliates by re‑valuing the world. Unable to strike the strong, the resentful soul rebrands its weakness as virtue. The resentful soul calls self-renunciation “good,” calling joyful self-expression “evil.” The psychic payoff leaves one clinging to one’s pain as the proof and the price of one’s righteousness. “I may be suffering, but at least I’m better than you”. Ressentiment is thus reactive, comparative, and subterranean. Ressentiment needs a rival the way a leech needs skin to suck on.

When the elder brother complains that “you never gave me a young goat”, Nietzsche sees the elder brother leading a moral life that is one long tally of owed gratification. When the elder brother says “I never disobeyed”, Nietzsche hears an act of self-canonization through self-negation. When the elder brother stands at the threshold of the party and refuses to enter, Nietzsche sees self-negation exposed as an act of revenge.

Twelve‑Step wisdom warns us that “resentment is the number‑one offender.” Like the elder son, many in recovery (including me!) launch their sober careers as joyless self-negators, convinced the spotlight should be on the precious specialness of their quiet heroism. It takes a lot of deliberate, public work to let go of that. The Step 4 moral inventory directly asks us to list resentments, then probe the fear and self‑seeking beneath each and every one. Often we discover an elder‑brother script running the show: If I’m good then life will pay out. When someone else receives mercy or joy that seems to us to be unearned, our hidden transaction with the universe is exposed.

As I see it, the solution isn’t to shame the feeling - it’s to name it, own it, and to re‑enter the party called “life on life’s terms.”

—

To see if you’re running an elder-brother script, ask yourself: whose good news felt like bad news to me?

Think of a single act of grace you can extend - a congratulation, an invitation, an apology, or a gift - then step across the threshold and join the celebration.