The horror of success and serenity

The Cremator (1969) depicts a moral nightmare that just won't leave me alone

The one word that best describes Dostoevsky's novels is "torment" - there are plenty of other words but that's the word that keeps me coming back to him. His most interesting characters are the ones who have rich and well-thought-out worldviews that are both intellectually compelling and psychologically unsustainable, characters who are torn in different directions by their minds and their hearts.

There's a comfort in that torment, though. Moral truth in Dostoevsky's universe has a way of asserting itself whether we like it or not. Nobody in his books can ultimately get away with collapsing into themselves.

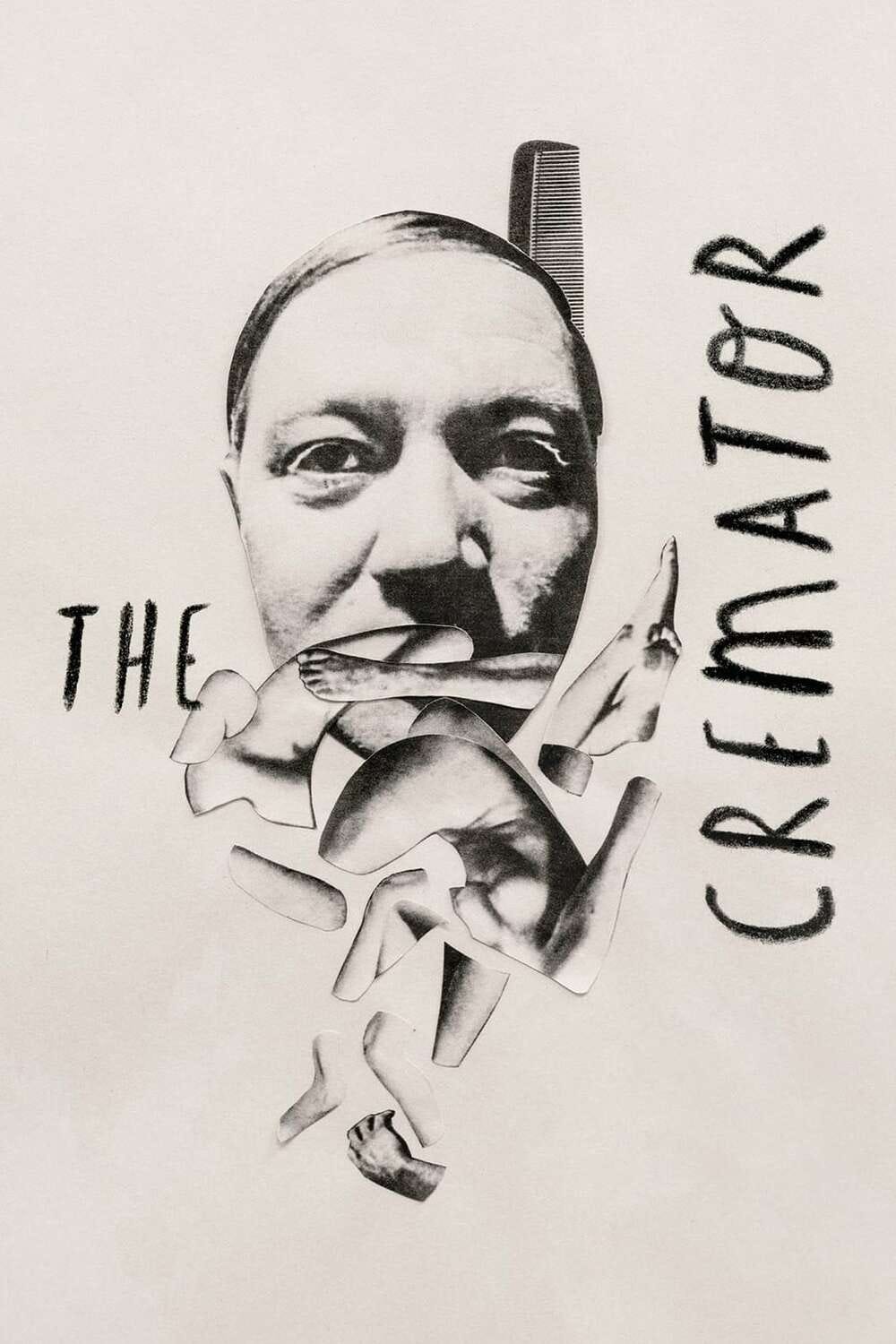

That's why I find stories like those in "The Cremator", a Czech film from 1969, to be so disturbing. Juraj Herz's expressionist masterpiece follows Karl Kopfrkingl, a crematorium worker in Prague during the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia, as his highfalutin ideals lead him to commit atrocities at every scale. Unlike Dostoevsky’s monsters, though, he seems to levitate with detachment from every monstrous act he commits.

Kopfrkingl, played with unsettling calm by Rudolf Hrušínský, sees himself as a liberator of souls, helping them transcend their earthly suffering through the purification of cremation. His moral framework is internally consistent and, to him, profoundly humanitarian. This framework remains consistent to him as the Nazis occupy his country and he drifts into the party and seamlessly integrates their ideology into his. His serenity is so complete that nothing disturbs him, not even the necessity of killing his Jewish family members. His commitment to the goodness of humanity is so abstract that any concrete action can satisfy that commitment, including genocide.

This is where “The Cremator” demonstrates a capacity for moral horror beyond what we find in Dostoevsky. In “Crime and Punishment”, Raskolnikov's theoretical justification for murder crumbles under the weight of actual killing, and he ends the book repentant. In “The Cremator”, Kopfrkingl ends the film with a shimmering vision of himself as the Dalai Lama in Tibet. He murders his Jewish wife and son not with the feverish desperation of Crime and Punishment's protagonist, but with the assured certainty of someone performing an obvious duty. There is no crack in his armor, no crack in his mirror, no rupture through which anything other than himself can make itself known.

I’m writing this after seeing the film - it was based off of a novel, which I haven’t yet read, but now very much want to. One of the things that compels me about the film is its style *as* a film, the play of the possibilities of the medium itself. Distorted angles and dreamlike sequences don’t depict psychological torment but directly depict the world as Kopfrkingl sees it – a nasty place where suffering is merely a temporary state to be transcended through his precious intervention. The film is mostly a monologue, sentences started in one scene and finished in the next, the people in the film perfectly interchangeable. The horror of the film isn’t in what it depicts, but in what it does not.

The totalitarian Nazi state is a big part of what makes this moral horror possible - Kopfrkringl’s atrocities receive full sanction from the powers that be. If anyone out there thinks he is doing something wrong, you can be sure that the authorities will never let him know about it. This is another dimension of the horror, for me - the idea that some measure of political victory will create a moral universe that doesn’t have an outside, where extremities and deformities will never be commented on since nobody is permitted to think about any other way of being. Perhaps this is what led the film to be censored by the Soviets, even though the Nazis were superficially the main villains.

Achieving political power is the ultimate dream for many, as is serenity, as is a vision of contributing to the highest good. What this film shows for me is not the horror of us failing in our quests, but the horror of us succeeding.

The deepest nightmare isn’t a life of tension between the head and the heart, but a life where our heart stops completely.